Defining Distinction With No Definition

Living as Hispanics in America brings culture infusion, basic struggles to fit in

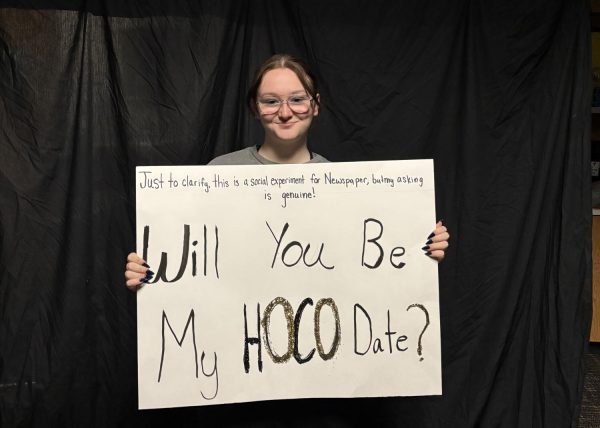

Defined by its mesmerizing beauty and rhythm, polleras is a type of dress worn in traditional dances, a clear example of Panamanian history that can be seen alongside many cultures across Latin America. Deysa Bennett performs a traditional dance with friends and family’s support.

Lush environments and colors with a defining fascination of culture and food, Hispanic culture is distinct in its own individuality, not tied to one place or person.

Stepping out of the spotlight towards the end of Hispanic Heritage Month, students are reminded of their identity in America as Hispanics.

“My first language was Spanish because my parents taught me that when I was about one to three-years-old,” sophomore Camillo Bermudez said. “Pre-K was the only time I was ever in any Spanish-speaking class. I was in there for maybe three days, and then I left to a normal English class.”

Though being born in America, Bermudez’s parents moved from Colombia to raise him with a fresh background.

“When I started school, nobody here spoke Spanish. My parents basically told me to scrap any Spanish that I knew and just learn all English, so because of that, I forgot most of my Spanish,” Bermudez said. “My parents found it a lot more valuable to learn English than to know Spanish at the time.”

For some, being a minority gives an identity that sticks out to most people in public and like most have experienced before, prejudice is always present.

“There’s been times where we’ve been out shopping, and someone has made assumptions about us and things like that. A lot of that I tend to push aside because I think that we’re all just people and it’s like they’re probably just mad at the moment, so I try to just shrug it off, ” Bermudez said.

According to the Pew Research Center in 2018, 38% of Hispanics in a 12-month gap say they have experienced a form racism, including verbal discrimination and even unfair treatment even if they have roots in the U.S.

“My dad was born in Mexico City, and my mom was born here in Texas,” junior Leah Juarez said. “I was born here in Shenandoah.”

While growing up, Juarez felt distant connections with her Hispanic roots.

“I try to be proud of who I am, and while still being Hispanic, I try to carry on my parents’ traditions,” Juarez said. “I still have a connection with my culture, but I feel like I have lost parts of me.”

Unlike many of her peers, interactions lack the charm of connection from her pushed back culture.

“I do feel disconnected though because I don’t speak Spanish,” Juarez said. “I wish I did- I just never learned, so when people talk to me in Spanish, I try to avoid staying because I feel left out.”

For Juarez, not being able to speak Spanish heavily influences the way that she sees the world and her family.

“At family gatherings, I feel like I can’t be fully happy because of my disconnection.

Losing parts of culture with being born in America, being born in different parts of the world creates an epicenter within a flourishing culture.

“I was born in Mexico City, and I lived there for eight years,” junior Sofia-Salas Sanchez said. “My parents are from Guadalajara. We lived there for eight years, Guadalajara for two years and then Mexico City for the rest of the time.”

While in Mexico, Salas-Sanchez attended a small private school for all her years there.

“We stayed in one classroom the entirety of elementary with one teacher. We didn’t change classes. Here, it was kind of similar because we switched teachers,” Salas-Sanchez said.

When moving to America, Salas-Sanchez only moved with her direct family, leaving behind direct connections with friends and family.

“We had no friends here when we first came, so all our celebrations were at home and with just our family, so it was completely different than what we’d known as children,” Salas-Sanchez said.

Around the beginning of November, many Spanish-speaking countries celebrate Día De Los Muertos, Day of the Dead, a time where families remember loved ones and ancestors.

“All the different holidays are weird, like Halloween. We celebrate Día De los Muertos,” Salas-Sanchez said. “Halloween is about trick-or-treating, but over there we do posadas, where we do kind of the same thing but with friends and family, not with little groups- it’s a whole community doing it. Here’s you just go with your friend group and go trick-or-treating with them.”

Met with cultural shocks left and right, holidays stood out in their different routines and looks.

“One day when I was in elementary school here, my mom made me Plátano Fritos for lunch, a Mexican desert where its banana and you fry it, and if you don’t know banana after a few hours, it gets soggy and smelly,” Salas-Sanchez said. “I was having lunch, and these white dudes started making fun of it. I remember having such trauma that I didn’t bring it for four years to school.”

While only being a smaller portion of the population, Hispanic traditions consist of cultures that stretch across all Latin America, not just adjacent and local neighbors.

“I was born in Argentina and lived there for six years. My entire family came with me because of a job offer for my dad,” sophomore Lucia Cando said. “Spanish is a lot different here. Nothing is spelled differently, but it’s an accent thing.”

Considering the local Spanish that has developed in Texas derives from neighboring countries and outside influences, Cando’s accent stands out, just one of the differing factors when moving an entire continent.

“I went to a Catholic Private school. It’s like here, but it’s different because the teachers came to your class, you didn’t change classes,” Cando said. “I had known these kids since I was two and those people never changed. Now it’s like every year people in these classes change.”

Even while getting used to new faces, Cando’s affection and friendliness never goes untouched in interactions.

“Socially, everyone’s way more affectionate in Argentina,” Cando said. “You literally greet someone by giving them a hug and kiss, even if you don’t know them. Over here it’s like a high five and a ‘Nice to meet you,’ and that’s it.”

Cando travels to Argentina every year to visit family and notices differences between cultures.

“We celebrate Christmas in Argentina once the clock hits 12, and a dad dresses up as Santa and brings the gifts, but over here you just wake up and there’s gifts,” Cando said. “We hangout and have dinner with the family and wait until 12. We also have Los Reyes Magos where you put shoes out and put water out for the camels. It’s only when you’re little, and it’s about Jesus.”

As a Catholic holiday, Los Tres Reyes Magos, the Three Wise Men, is one different holiday that commemorates the arrival of the three kings for the birth of Jesus. The holiday is celebrated for children with gifts and food as symbols for the kings. But other differences are obvious, too.

“One time in the 7th grade, I did a whole project about Argentina with a map and everything, and they still asked me what part of Mexico I was from,” Cando said. “I feel like in the US nowhere is shown enough except for the US. You could ask someone to point out Europe on the map and they wouldn’t even know where Europe is. I feel like the U.S. is like the least cultured about that.”

For immigrating parents, many hope to raise their children with better opportunities that was not directly present in their home country.

“I was born in Texas; both my parents are Panamanian. My mother is half indigenous and half Panamanian. My dad is of African descent but from Panama. He lived in Panama until he was 10 and moved to the U.S. and then to the Puerto Rico and then back here,” sophomore Deysa Bennett said. “I’ve been [to Panama] twice — once when I was four and once when I was seven.”

Living in a mixed Hispanic household, Bennett still grew up with a Spanish tongue.

“I did grow up learning Spanish, but I stopped speaking it after kids bullied me. I was fluent in both English and Spanish as much as a toddler could be, but because my dad is of African descent, I also look that, so they thought it was weird a black girl would speak Spanish.”

According to the Pew Research Center in May 2022, Afro-Latino adults make up only 2% of the US population, 12% of which that do not identify as Hispanic at all.

“As an Afro-Latina, people look at me and assume I’m black. I don’t get that inclusion of being Hispanic unless I say something,” Bennett said. “From my family, my Hispanic family tells my I’m not Hispanic enough, or my black family tells me I’m not black enough.

While only being part of a small group of individuals in the US, Bennett ensures to keep her Hispanic identity.

“I call myself Afro-Latina because I don’t want to forget my African descent. A lot of Americans don’t recognize Afro-Latinos as Latino people,” Bennett said. “Panama in general is not represented. People don’t realize Afro-Latinos exist and that it’s a genuine thing.”

From her father’s family living their lives in the U.S., Bennett feels more influence of her black culture on her father’s side rather than her mother that stuck with her Panamanian roots.

“Sticking out gives me an identity. People are surprised that I’m Hispanic saying how I don’t look like it, and it certainly surprises people,” Bennett said. “I want to be more involved with my culture but being a first-generation kid, it’s kind of hard because your parents are so used to the idea of having to fit in that they kind of forget themselves and being Hispanic.”